The Narrative Disruptions of 'I Deliver Parcels in Beijing'

It’s common knowledge that literature is not about work: it’s about vocation, that thorny word, denoting one’s money-blind choice in profession. (For if you’re adequately compensated for your labor, doesn’t that diminish the authenticity of your passion?) Most of the heroes of contemporary fiction are graduate students, writers, or editors at publishing houses, all of whom are supremely jaded about their craft and contorting their income into unfavorable housing situations. Otherwise the hero has assumed an administrative position at a “firm,” whose relevance is increasingly conquered by their personal issues.

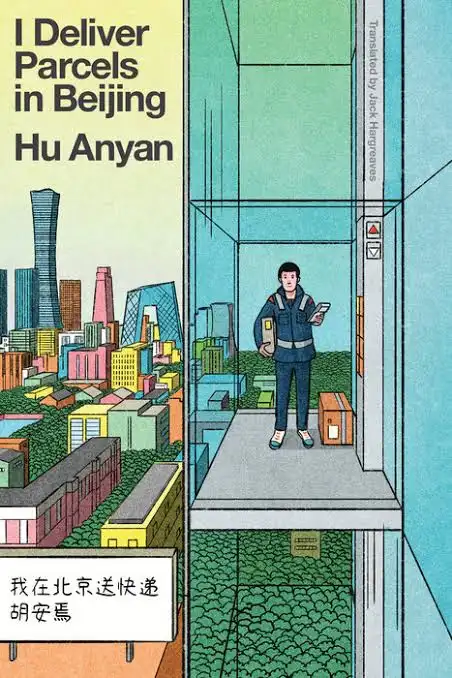

Hu Anyan’s I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is a departure from this literary tradition that has largely been rooted in the West. It begins by recounting Anyan’s experience as a night-shift worker in a logistics warehouse, after which he became a deliveryman in Beijing and then drifted from one job to another in Shanghai. After these deep dives into three of his positions, Anyan returns to the beginning to list the nineteen jobs that he’s had in his life—including as a hotel waiter, a clothing store assistant, and a graphic designer—to create a serviceable biography that largely excludes mentions of his family, romantic life, and childhood.

Anyan’s memoir stands out among the literary fiction titles of today. In her essay “Contemporary Literature is Haunted by an Absence of Money,” YA novelist Naomi Kanakia contrasts her experiences reading 19th-century novels with their counterparts that begin to emerge among the writers of the Lost Generation. Compared to Mr. Bennet’s £2,000 a year income in Pride and Prejudice, the financial means of the main circle in The Sun Also Rises are much more muddy—although it’s clearly no object to their leisurely lifestyles.

In the 21st century, this phenomenon has ossified into literary norm. In Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, perhaps the most influential book of its genre, the protagonist is able to spend an entire year sleeping with minimal financial strain. The main character of Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding is a non-practicing psychoanalyst who lives alone in Belleville, Paris, a formerly working-class village that has since been gentrified. Both are stories that epitomize the Western ideal of the “psychological novel,” which was pioneered most memorably in Europe by Madame de La Fayette’s La Princesse de Clèves and, later, in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela.

“Perhaps it is the upper- and upper-middle-class itself that desires these dramas,” Kanakia muses. “They want to read about self-determining individuals who are stymied only by their own internal conflict. But…I can’t see why we should want such a thing when in our daily lives we are so aware that this is simply not how the world works.” Of course, I Deliver Parcels in Beijing differs from the previous titles I mentioned in that Anyan writes directly from his own experiences, without any pressure to fictionalize it for narrative effect. However, coming from an individual with minimal fame prior to the book’s publication, the success of his book in both China and the West suggests a shift in the type of literature that people are interested in reading.

What’s clear is that Anyan’s book is not an ordinary memoir. In a society that encourages the compartmentalization of work from one’s identity—unless it is, of course, a noble “vocation”—to dwell on one’s employment seems a masochistic use of one’s time. However, this is the reality for people working within the gig economy sector, whose freelance-driven labor transforms their time into an endless expanse of potential earnings. While this is the standard critique of gig work, it still overlooks the more insidious mechanisms at the heart of its labor—which are only communicable by people who have experienced it.

Anyan reveals that the organizational structures of many companies force delivery workers to hustle far harder than if their compensation was tied solely to the payments received from their deliveries. He remembers that one of his managers “…demanded that we invite customers to award us a five-star rating after every successful delivery. There was a table that showed our employee stats stuck up in the depot. On it, they updated our daily ratings, and the lower-ranked colleagues would be singled out during meetings.” Comparison between workers never ended at company-wide censure: high-efficiency workers were often granted more bonuses. Many workers ignored their personal well-being in order to keep pace with constantly rising expectations.

After contracting pneumonia and receiving clear instructions to rest from his doctor, Anyan waited anxiously for the moment that he could return to work, ignoring medical advice. “I didn’t go back for a follow-up as instructed,” he wrote. “I was afraid the doctor would want me to do another CT scan. The first one had cost me three hundred yuan. I did the calculations later and worked out that, considering the missed days of work, this single period of illness set me back three thousand yuan, which was what I earned in half a month.” With no baseline protections for gig workers—such as sick leave or benefits—earning less money is framed as a personal failure of motivation, rather than the result of a system that profits from keeping its workers underpaid and overworked.

However, Anyan is not in the business of indicting the gig economy. The anecdotes are meandering, repetitive, and often long-winded—a choice that would make far less sense if the book were centered around a specific thesis. Although many critics have pointed to Anyan’s discursive approach as off-putting, it ultimately strengthens the embodied feeling that permeates the text.

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing suggests what contemporary literature can be: a medium for the ordinary individual to convey their life experiences as an end in itself, rather than as a means of extracting larger truths. Contrasting the Western “psychological novel,” the Japanese I-novel is a confessional genre that enabled writers to discuss topics otherwise considered taboo. Rather than positioning the self as detached from external conditions, the I-novel recognizes the world as an essential force in shaping identity. Anyan channels this ethos precisely: by focusing on his work life, he asserts its all-consuming impact on his sense of self. And perhaps this resonates beyond him. For what is life, if not a never-ending monologue about one’s issues at work?

Regardless of whether Anyan explicitly engages with the societal dimensions of the gig economy, its broader implications are clear. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions reports that workers in “new forms of employment” now comprise 21% of the nation’s workforce—more than 84 million people. Many are rural youth migrating to cities, recent graduates unable to find stable employment, or workers suddenly laid off. This swelling labor force has depressed wages and intensified competition, while climate change–induced extreme weather makes delivery work even more dangerous. Similar scenes unfold in New York, where delivery workers skid through streets during record-breaking rainfall.

To criticize the gig industry is not to invalidate the years Hu Anyan dedicated to his work before becoming a full-time writer. A reserved figure, Anyan rarely expresses bitterness, instead recounting fleeting frustrations with coworkers or workplace conditions. To acknowledge moments of satisfaction is not to absolve the system of its cruelty; to exclude them would amputate what makes the book exceptional—its completeness.

“I’d like to sum up my time as a courier as follows, and it’s no exaggeration: I was once the best courier that some customers have ever seen,” Anyan writes. I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is charming, sobering, and completely engrossing—and unmistakably his.