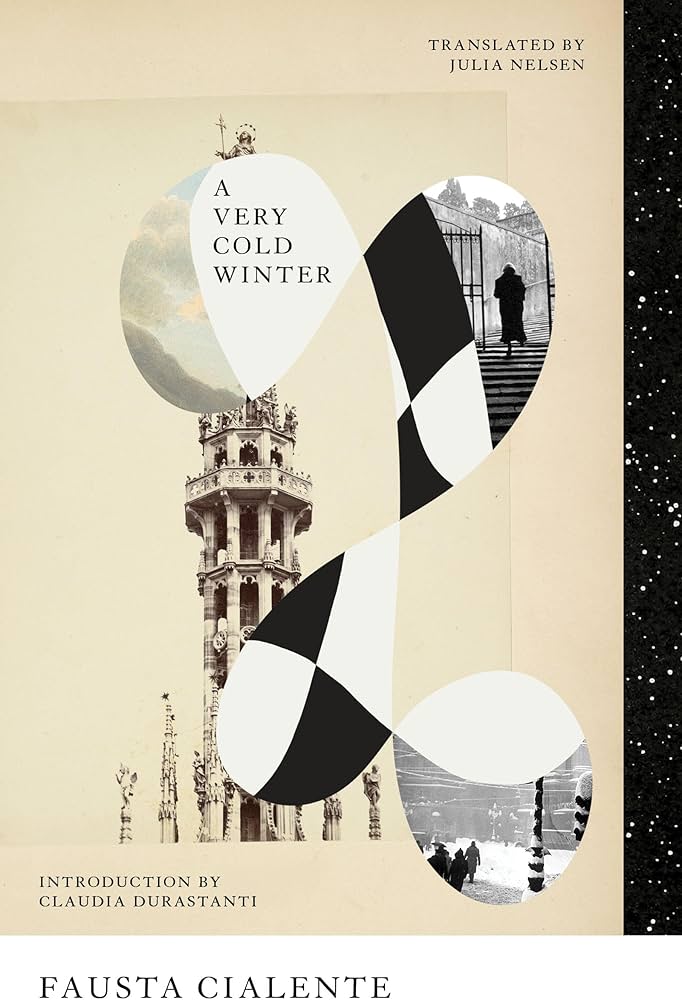

Time Ruins in 'A Very Cold Winter'

The story is disguised under the trappings of a domestic drama. Fausta Cialente’s A Very Cold Winter is set in the ruins of post-war Milan, where a family prepares to spend the winter in an illegally-occupied attic. Although the novel’s themes purport to conform to typical seasonal rhythms, Cialente steers the plot into a much darker and pensive place.

The canon of Italian literature is studded with works concerning both war and domestic life, many of which have received international acclaim. The darling of Mariner Classics, Italo Calvino wrote trim fabulistic novels that channeled his experience as an Italian Resistance fighter; moreover, New York Review Books has kept Nataliza Ginzburg, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Elsa Morante in the spotlight, cementing them as authors indispensable to achieving a kind of worldly literary caché. More recently, Elena Ferrante’s oeuvre has dominated both literary and commercial circles, her rich prose and subtle pulpiness fusing to create the kind of respectable market sensation that most editors can only dream of.

Compared to her contemporaries, Fausta Cialente has slipped through the cracks (not least since she has remained largely untranslated into English). Although she was born and raised in Sardinia and then Trieste, she moved to Alexandria for twenty years after marrying the Egyptian-born Italian composer Enrico Terni. However, she still remained a prominent member of the Italian Anti-Fascist Movement, as well as a staunch feminist, throughout her life.

Although Claudia Durastanti, the writer of the book’s introduction, claims it as part of the feminist Italian tradition—and indeed, the book has been described as following the fate of women in the post-war era, who assume the “burden of survival” since their husbands are either dead or gone—to describe it as primarily a “feminist novel” would be to misrepresent the book’s intended scope. (It should also be noted that Cialente’s writing precedes the zenith of Italy’s feminist movement by around a decade.)

The book begins with a sense of strain: Camilla, the matriarch, must steer her three children and extended family through a period of intense poverty and hardship through the war. While she tries to maintain a semblance of normal family life, the war has eradicated that possibility: her nephew, Nicola, has been killed in the war, leaving a wife and infant daughter; Camilla’s husband, moreover, disappeared several years earlier.

As time passes, the family unit fractures, however whether this is for the best remains one of the novel’s central moral ambiguities. The new possibilities for female agency that the war inadvertently engenders is counterbalanced by a crisis in male identity, as they return from the warfront to a world where they are beholden to women. Enzo, the family’s neighbor whom they absorb into their community, does little to combat his feelings of alienation; Camilla’s nephew, Arrigo, appears largely oblivious to the snobbery of his wife, Milena; and Guido, Camilla’s youngest, is too little to exercise any real agency, his thespian aspirations remaining unattainable.

While men languish in ambivalence, the family’s women wrestle between their pursuit of independence and their domestic obligations, both real and aspirational. Their personal victories are counterbalanced by feelings of betrayal from the people around them. The cannibalistic machine of the nuclear family animates the novel from start to finish, both vicious and tender.

Although the book’s premise is unassuming, it distinguishes itself by Cialente’s remarkable ability to articulate the mundane scandals of life in different registers. Whether writing from the perspective of a world-weary matron, an enterprising adolescent, or a curious young boy, Cialente embodies each character effortlessly and without reserve. Flitting between perspectives, the readers’ investment in the individual characters is just as much about the various relationships between them that are brought to life in these pages. While domestic portraits often veer into sentimentality, Cialente eschews this avenue to opt for a more realist tone that treats the love between family members as scenery instead of destination.

A Very Cold Winter is also a feat of incredible translation. Julia Nelsen captures sentences of pure exquisiteness, her process channeling translation’s dual ethos of both preservation and creation. As a monolingual reader, international literature can be a taxing endeavour: I am usually left hungering for the book’s original language, certain that I can intuit the moments of lost meaning. However I often found myself arrested by Nelsen’s prose, taken in by what is both her and Cialente and the timelessness of a story deeply rooted in the context of fascism and the Second World War. That I barely considered the translated aspect of this story is a testament to Nelsen’s subtle, masterful technique.

The lesson of A Very Cold Winter is that life will transcend its cycles: those who wait for spring will be disappointed to find the world too changed for its return. War has a tendency to exacerbate these temporal glitches. However, is what emerges in its place all poison, since it doesn’t honor the coherence of the past? This novel paces the poles between anger and frustration that we all know, attempting to find a place of peace.